I’ve always loved airplanes. This almost certainly stems from being the son of a pilot, and it’s an interest that has stayed with me my whole life. From my dad taking a 5-year old Jakob to the airport to watch the airplanes, all the way to me spending hundreds of hours of my free time researching, creating and practicing an hour-long conference talk on things us developers should learn from the aviation industry.

So naturally, being a pilot was high on my career wish list. It actually wasn’t until high school that it got bumped off the #1 spot. After getting to jump-seat in the cockpit with my dad for dozens of flights and logging an unhealthy number of hours in flight sim I came to the conclusion that, while I still found planes incredibly cool, a career choice as a pilot would probably be too repetitive for the type of brain I have.

I’m the sort of person who gets completely obsessed with things, whether it’s a hobby project, a video game I’ve gotten into, or a piece of music (ask me how many hours I spent listening to Rachmaninov’s 3rd piano concerto in 2024). After a while, my obsession dies down somewhat, my attention craves something new, and the cycle starts over again.

While pilots certainly do face new challenges at work, with different combinations of technical, environmental and human factors they have to contend with, they fundamentally do the same thing pretty much every day. Their procedures are, by design and for the sake of safety, incredibly standardized. As I was charting my path in life in my late teens, I added up these two factors and concluded that while tempting, a career as a pilot probably wasn’t for me.

The privilege of constant stupidity

A career as a software engineer, on the other hand, represents an infinite supply of new responsibilities and concepts to learn. Virtually every industry in the world needs IT, and as software engineers we potentially need to understand everything from product strategy and team management to complex mathematics and the inner, physical workings of a processor. That is to say, the field possesses both incredible width and depth.

My experience is that, as long as you’re willing to step outside your comfort zone, a programming job can act as an infinite supply of things to learn. Granted, I’m still far from being at the end of my career, but in talking to colleagues who have been doing this for decades, I don’t get the impression that they’ve run out of things to explore either. In other words, I’m pretty confident I will feel the same way about this specific thing when I’m old, gray, and tired of getting styled on by 20-something hotshot programmers. That’s a big reason why I chose computer science in university, why I settled on a career as a software engineer, and why I haven’t looked back (or rather, up) ever since.

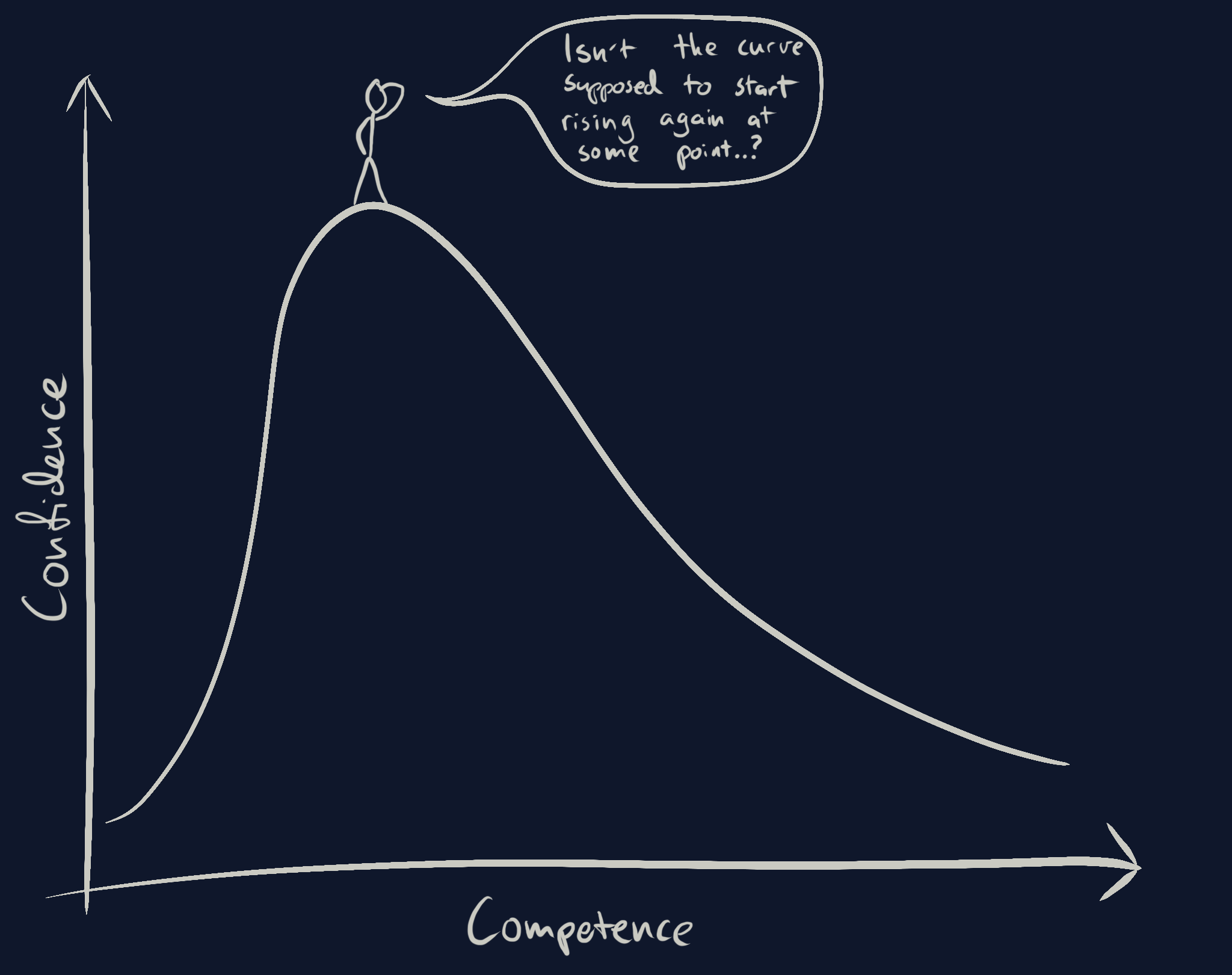

Because being in a field where it’s completely impossible to run out of things to learn is a huge privilege, and I know that it’s something I sometimes take for granted. There are even some times where I, in the back of my mind, curse how wide and deep our field goes. Because it comes pre-packaged with what sometimes feels like an infinitely long downhill “Dunning-Kruger graph”.

Before you lambast me: Yes, this graph is a spin-off of the meme variant of the Dunning-Kruger effect graph. That’s on purpose. The graph describing the actual effect looks like this, and makes for a much less potent metaphor.

This is all to say that as long as you haven’t purposefully walled yourself off in a garden of comfort, you’re gonna have to get used to feeling stupid as a developer. There are almost always going to be deeper levels to what you’re doing, which you won’t immediately understand, and I would be lying if I said it never affects my confidence. My view is that this is just something we have to come to terms with; the price we pay for always having an endless supply of things to learn.

I think that this effect hits junior developers the hardest. The combination of neither having years of built-up confidence nor a decent level of knowledge of a wide array of topics is a perfect storm for letting yourself be negatively affected by this feeling. When it inevitably arrives, I think people mostly react in two different ways:

#1: That fucking meme with the dog

They bang their head against the difficult concept until they reach a certain, critical point, and proceed to give up. The giving-up can come in all shapes and sizes; trawling the internet for a prefab solution while forgoing understanding (anyone remember Stack Overflow?), mindless LLM prompting, or passing the task off to someone else. The way that it happens doesn’t really matter, they’re all forms of capitulation to imposter syndrome—declarations of intellectual bankruptcy. This sort of self-pity is understandable, but entirely self-sabotaging. It feeds on lack of confidence, and lowers the barrier to further self-pity and capitulation.

This is made worse when their peers reassure them that nobody really knows what they’re doing. Because in fact, a lot of people do actually know what they’re doing. Understanding difficult things is possible. Mastery is possible. Ruby on Rails-inventor and chronic strong-opinion-haver David Heinemeier Hansson goes on an excellent rant about this in an episode of the TopShelf podcast, as he shares his infuriation with “that fucking meme with the dog” (effectively the mascot for this type of behavior). Every time somebody who does in fact know what they’re doing posts that fucking meme, they make this sort of reaction to resistance more acceptable.

If you believe that most of your peers don’t know their shit, why would you expect better of yourself? Why would you embark on the journey towards genuine understanding when it’s filled with self-doubt you don’t otherwise need to face?

#2: The uncomfortable path of unstupification

The alternative is to get fucking good. I know that sounds emotionally constipated enough to be the title of a best-selling self-help book you’d find in an airport book store, but that’s really all there is to it. You can accept that it will continue to make you feel stupid, but press on anyways, as you rage against the dying of your intellectual integrity. There are different ways of doing this, of course, ranging from the quite inefficient “smash your head against the problem until you get it” to the more reasonable “ask someone smart to explain it”, but the common denominator is that they all require you to face the fact that you don’t get it. Not only do you have to face it, you probably have to live with it hanging over your shoulder for a good while, so you’d best get to know each other properly.

Now, I am by no means saying that people fall into only one of these two categories. I’ve spent plenty of time in the first one, and still do from time to time. But when I notice it happening I try to remind myself that it’s just more fun to be competent. With time, this has made me much more comfortable with not knowing, and I notice that I am significantly more likely these days to ask a coworker a “stupid” question about something I’m supposed to know. I’ve also noticed that the people around me who ask the highest number of “stupid questions” are, without exception, the most skilled developers I work with (more on that later).

The root of these reflections

There is a specific reason for why I’ve been thinking about this recently: Around three months ago I changed jobs and started to work as a developer in an airline (seems like I got the best of both worlds, eh?). I’d been in the same company for three years, even staying with the same team the entire time. There, I had the privilege of working with some of the smartest, most knowledgable people I’ve ever met. Having now parted ways with them (at least professionally), I’ve found myself thinking about how I can make sure that I follow a path similar to theirs, as I get older and more experienced.

I had many colleagues I looked up to in that job, but I want to highlight two of them, Robin and Karl Yngve (they both have fantastic blogs, which you should check out by clicking on their hyperlinked names). Robin is an experienced and extremely knowledgable developer, with a patience and pedagogic ability I’ve yet to see anyone match. Karl Yngve, interestingly, only has a few more months of experience as a professional developer than I do, but has plenty of programming experience from his decade-long career as a mathematician and researcher.

Despite having very different backgrounds, they both share a superpower: They are, or at least act as if they are, fearless in the face of situations that threaten to expose holes in their knowledge. It’s not a case of them knowing “everything”–in fact, they are probably the two developers I’ve worked with who have been the most open about the things they don’t know. Rather, they seem to always be completely convinced that they can learn the stuff they need in order to complete the task at hand. It’s not hubris, but rather a sort of “intellectual confidence”.

Because of this attitude they are exposed to more novel problems than the people around them, and as a consequence, I think they build knowledge that’s both wider, and deeper than otherwise. As you might imagine, this is a bit of a chicken-or-egg situation. The knowledge they build in this way, and their success in tackling new problems, makes them more likely to take on yet more new challenges. It’s a positive feedback loop that can only start with a leap of faith. As cheesy as it sounds, it requires a bet on oneself.

As previously mentioned, these reflections are fairly new to me. It’s only recently, due to the job change, that I’ve really been actively thinking about this. With that said, I think I’ve unconsciously tried to employ this mindset for a while, at least in certain situations. The best example is probably conference speaking, a field that was completely new to me just one and a half years ago, where I now feel like I’ve built a fair degree of both confidence and competence.

Straight up not a good time

That’s not to say that I don’t also have experience with the opposite. During most of my five-year period as a student, I was pretty insecure about my skills as a programmer and engineer. It’s not that my grades were terrible–I did okay in most subjects–but I struggled with actually understanding the curriculum. I felt no sense of mastery. On the surface level, the issue was pretty clear: I wasn’t dedicating nearly enough time to going to lectures, doing coursework and preparing for exams.

Looking at how I spent my days instead (largely in front of my computer, often playing video games) it’s easy to conclude that I just didn’t bother doing the work, that I didn’t have the discipline I needed at the time. That’s partially correct, but I think the barrier I struggled with wasn’t motivation, laziness or interest for my courses, but rather the fact that I was deeply uncomfortable with how little I understood whenever I sat down to work on the obligatory coursework.

This was at its worst during exam season. Almost without exception, I would put off studying until the day before the exam. That’s the point where my fear of showing up at the exam with zero knowledge finally surpassed my fear of my own incompetence, and forced me to face the latter. It’s hard to overstate how much this cycle sucked, and I feel lucky that it didn’t wreck my grades (or psyche) as much as it could (and probably should) have. Worse yet, I was–even at the time–fully aware that this problem was entirely self-imposed, and it felt downright embarrassing to struggle with it. As a result, I didn’t talk about it with anyone. In hindsight, that was probably the worst thing I could do. In sharing drafts of this blog post, I’ve had people I know to be phenomenally skilled share with me that they’ve experienced the exact same cycle. Had I known as a student that I wasn’t the only one struggling with this, it would have probably been much easier to face.

It was only towards the end of my studies, as I was working on my master’s degree, that it got somewhat better. In the last semesters of my computer science program, there was a deliberate shift towards group project-based courses, away from more traditional exam-based ones. These had few or no lectures, and usually no exam. They consisted entirely of your group being assigned a problem at the start of the semester, which you were expected to work on together for the next few months. Back in my day this ranged from writing database adapters and multiplayer android games to development of actual applications for real clients.

I would assume that the words “group project” has some shivers going down some spines, but for me they were very, very helpful. Partially because of the obvious effects, such as having access to people I could learn from. I was quite shy back in those days (I still can be at times, but I’m much better at managing it now), and hadn’t made many friends during my first years of university. Pretty much everyone I still keep in contact with from those days are ones I was randomly assigned into groups with. But more importantly for this story, being part of a group made it so I suddenly had other people depend on me. Turns out that’s a potent drug for my brain in particular. More than anything else, I was driven by not wanting to disappoint. That fear was stronger than the aforementioned fear of facing my own incompetence.

A new hope

This was how I finally managed to short-circuit the negative spiral I had been trapped in for most of my five years in university. Having an external motivator (or fear, depending on how you look at it) helped me get over the “hump of discomfort”, and started a positive feedback loop. With the help of knowledgable classmates, I got experience with technology I hadn’t tried before (React and TypeScript, for example). While this didn’t exactly provide any feelings of mastery, it became an important foundation for later.

Fast-forward a year or so, and I’m on the hunt for my first job. Compared to my peers, I was quite late, only starting the process of sending applications around half a year before graduation.

Also unlike my peers, I didn’t really know anything about any of the companies that were hiring developers. I hadn’t done any internships, didn’t have any connections in the industry, and had been very bad at attending career fairs and the like. I was therefore completely at the mercy of job listings. I sent out a handful of applications, effectively at random, and went to every interview I was invited to.

I’m pretty sure that my actual programming skills at this point were mediocre at absolute best, but luckily, I’ve always been good at explaining my thoughts and discussing theory (I’m pretty sure this stems from my tutoring experience–I tutored in math and physics as a side gig during my studies). This ability carried me through my interviews, and at the end of it all I had quite a few offers to choose from.

Even with my complete lack of knowledge about the Norwegian IT market, it was clear that one of the companies offering me a job was not like the others. It was a fairly new, fast-growing consultancy firm of around 30 people, which practiced a radical openness and hunger for learning that I’m yet to see matched anywhere else. The company has changed quite a bit as it has grown, and neither was nor is perfect (maybe I’ll write about that someday), but it was exactly the sort of place I needed. Looking back, I think it was pretty much the perfect first job for me, and considering the fact that I knew nothing about the places I was applying to, it’s fair to say that I lucked out.

The company was big enough that I had a bunch of knowledgable colleagues who were eager to help, but small enough that there were a lot of opportunities to take on responsibility, even for a fresh recruit. I was encouraged to involve myself in the running of the company, and soon found myself joining, and eventually also leading interviews of new developers. At the same time I was getting more and more comfortable taking on challenges on the technical side of things, and quickly got responsibility there too; responsibility which I believe I mostly lived up to.

I was encouraged to push the boundaries of my comfort zone, but always had the support I needed around me. This was what finally, decisively, moved me from a negative feedback loop to a positive one. I built up the confidence to take on more and more challenges, and with it, built more and more confidence.

A note on discipline

While it’s good to understand the importance of being competent, I believe a second ingredient is needed to get the most out of the positive feedback loop I’ve described: Discipline. Specifically, the discipline to actually apply this philosophy by taking the time to learn new concepts you come across. In the short term, this will slow you down, and it will require you to be comfortable with facing your lack of knowledge all of the time, rather than just some of the time.

This is something Karl Yngve, the previously mentioned scientist-turned-programmer, is excellent at. It really seems like it’s second nature to him, and I formally implore him to write a post on his own blog explaining how that came to be.

I’m still not great at this. More often than I would like, I take the shortcut of throwing stuff at the wall or going to an LLM, without really understanding all the precursors required to get there, and thus leave a hole in my knowledge.

In a few years I can hopefully publish a post here talking about how I finally managed to build the discipline required to extract closer to 100% of the available learning from my day-to-day encounters with stuff I don’t know. But for now, we will have to leave it here. Maybe that’s a good thing, this post is already twice as long as I planned.

A note on chainsaws

This topic is really big enough for a blog post of its own, but I feel like I have to include a thought on how artificial intelligence fits into all of this. My number one fear regarding AI developer tools is how it affects the growth of students and juniors, and it has everything to do with the things I’ve described in this blog post.

If used thoughtfully, there is no doubt in my mind that it can be a tool for greater learning, but I also know that if the tools we have to today had been available when I was struggling with something in university, I would have had the world’s best super-crutch to lean on. I think there’s a very real chance that it would’ve taken me way longer to escape the “I don’t know what I’m doing and I’m afraid to find out”-spiral, and I worry for today’s students. What’s gonna make the 19-year-old who’s insecure about their abilities face that insecurity head-on, when there is an alternative right there? I genuinely don’t know what the solution to this is, and I feel fortunate that I was forced to face this at a time when the most efficient way of avoiding using my brain was trawling Stack Overflow. In short? I think the newer generations are probably fucked.

Take heed, young padawan

We have the privilege of working in a field where there is an infinitely deep pool of knowledge to drink from. It has its disadvantages, but I sure as hell wouldn’t be without it. So whenever you feel like you’re sinking, remember the following:

It’s okay to be clueless, to not know, and to not understand. Every single person who is good at anything, including all of the people you look up to, started out that way. Not understanding the things you work with is uncomfortable, and it’s supposed to be. The only sustainable way to mend that feeling of discomfort is to accept the fact that you don’t understand, and decide to do something about it. Don’t resign yourself to a life of not getting it. You should do better, and you can do better.

And if it takes a while to stick, that’s okay. The message above is as much of a reminder to my future self as it is advice to anyone else.