One of the biggest system shocks I experienced when I started out working as a software engineer and consultant was the silly number of trailing zeroes you see every time money is involved. I remember picking the cheapest ticket options on inconvenient flights in order to save the company a few dozen dollars, even when the money saved equalled something like 15 minutes of client billing. Eventually I got used to the fact that not all money is created equal, and that — while you should obviously be smart with company money — worrying about every single nickel and dime is not only a silly thing to stress over but a waste of time (and therefore money).

As new graduates started in the years after me I got the chance to help them discover this sooner rather than later, and in that, hopefully helping them avoid some of the stress I experienced on the path to this particular insight. During these conversations I’ve found myself often returning to the phrase Monopoly money when talking about the sums businesses operate with, since viewing them with eyes calibrated by personal economy will make all numbers seem outrageously high.

Because in the end, it all depends on what kinds of numbers you’re used to seeing, right? As a student I worked a part-time private teacher gig, and was pretty damn happy with my roughly $20 hourly wage. In my mind, that was a good amount of money to make in an hour, and although the actual hourly wage was probably lower since any good private teacher will need to spend time preparing lessons, an unpaid activity in the company I part-timed at, I was satisfied.

It was absolutely wild to go from that to the Norwegian IT consultant industry, where a junior consultant straight out of school on a long-term full-time contract costs clients around $100 an hour. It brought with it a whole host of worries about how the hell I was supposed to justify that kind of insane price (that’s a story for another time), but eventually, with time, I got used to seeing that number too. Now I don’t even blink if a senior consultant tells me their hourly rate is $200, because while it’s still outrageously expensive, that’s just the order of magnitude this industry operates in.

Speed blindness

Anyone who’s driven on a highway knows that in the minutes after exiting the highway it’s very easy to go over the speed limit. Our brains do this funny thing where they get used to seeing the world whizz by at highway speeds. This effect is so powerful that before we have time to readjust, cruising at a cool 80 kilometers per hour (that’s 50 freedom units), a speed at which a crash can very much still kill you, can have you feeling like you’re just barely crawling along at the speed of a snail. I think the same thing happens with money. You get used to seeing that a certain expense is a certain very large number, just like you get used to highway speeds.

Okay, granted, this is hardly some big revelation. Obviously people will view a number differently based on which expense it represents. It’s when we start looking at decisions that impact multiple expenses that it gets interesting for me. Because a lot of the time expenses in one category will impact expenses in other categories. Spending $500 more in one area might for example save you $1,000 in another. Yet, and I think this often comes down to the speed blindness effect I mentioned, if the $500 increase is to a small budget post and the $1,000 affects a large one, a lot of people lose track of the fact that it’s still a $500 net gain. They see a huge relative increase in one area and a tiny relative decrease in another, and compare percentages rather than actual numbers.

Now, this is obviously an extreme example, and any rational manager presented with this choice would obviously happily spend the $500 to save $1,000. The trouble is that there are at least two more factors that complicate things. Firstly, while some costs (ie. a software license) might be concrete, many others are shrouded in uncertainty (ie. how much money said software will save the company). Secondly, it’s also pretty common that at least one side of this equation isn’t in dollars or pounds at all, but some abstract representation of money, such as developer time.

All expenses are equal, but some expenses are more equal than others

Because it’s when we start looking at developer time that it often gets difficult, isn’t it, whether we’re trying to predict the cost of a project or whether a purchase will pay for itself in the form of time saved down the line. My impression is that this is where a lot of decision makers get tripped up. I think this is because developer time checks all the “complicates-making-good-financial-decisions” checkboxes I’ve previously mentioned:

- Payroll is a massive cost, so something that would be a substantial cut to any other budget post might seem less significant when applied to payroll.

- It’s often difficult to give even a rough estimate of how much developer time will be saved due to a certain change, never mind an exact number.

- The fact that we’re talking about time, not dollars, exploits a weakness in our brains. This is one of the reasons you pay for things with “Riot points” instead of actual money in the in-game shop of League of Legends and other games like it. Our brains are really bad at translating this to a cost-context we’re used to, even if the math is exceedingly simple.

So for the rest of this blog post I’d like to focus on three areas where this payroll fallacy often rears its ugly head.

It’s one developer platform, Michael, what could it cost? Ten dollars?

We’re gonna start with what’s probably the most obvious example of deciding between development time and concrete costs. The age-old question: Build or buy?

Build-or-buy-decisions are a dime a dozen in our industry, but let’s take a look at one example: Using a managed hosting solution like Vercel for your applications versus building a platform where your developers can go from source code to live web application with minimum fuzz. Let’s say that we go for a very small platform team of 4ish developers, and let’s assume that they’re good enough at self-managing that you don’t need any auxiliary roles in the team. At the very least, that’s gonna run you (in Norway) somewhere around $500,000 a year just in wages, fees, taxes, pensions, and other obligatory costs. If you’re an organization with more than a few development teams working on different products, I can guarantee that a 4-person platform team will be a bottleneck, so I’d argue these numbers are very conservative on my part.

Do you have any fucking idea about how much Vercel you can buy for $500k a year?

No? You don’t?

Well, luckily for you you’re reading this on a blog running on good ol’ code, which means I can make a calculator that makes it abundantly clear how much Vercel half a million bucks gets you.

ShowHide calculation

| Item | Cost breakdown |

| Edge Request: | |

| Fast Data Transfer: | |

| Fast Origin Transfer: | |

| Function Invocations: | |

| Function Duration: | |

This is a very rough estimate of how much Vercel traffic you'll get for a given price. It's based on my own page's usage, but based on what I've seen online it's probably not orders of magnitude off. Cost obviously varies massively based on what kind of website we're talking about, how well optimized it is for Vercel, and how users use it. But we all understand that, so I'll stop disclaiming now.

That’s a lot of developer licenses and a fat chunk of traffic on a platform that’s not exactly known for being cheap. And remember, this is just the platform team’s payroll. You also need to pay for the actual servers you’ll run your stuff on. The point is that the math just doesn’t make sense until you hit a certain (very high) volume of traffic.

And yes there are absolutely other advantages to building your own platform (or CMS, or observability solution, etc.), even if the financials don’t justify it directly. The best tip I’ve heard says that you should build the things that give your product a competitive advantage, and buy the parts that just need to be as good as your competitors. If you’re building a Youtube competitor, you should probably build the video streaming tech in order to make it possible to have a significant advantage over competing sites, but you can get away with buying an auth solution. In other (oft-repeated) words: Buy for parity, build for competitive advantage.

As a developer who by nature really does like building things, I’m not trying to say you should always lean towards buying a solution, not at all. But I am saying we oughta get better at considering whether it’s really a good idea to spend 9 months understanding the intricacies of a payment system just because we didn’t want to give Stripe a cut.

Don’t skimp on RAM for your circular saw

As I mentioned at the start of this post, my entry into the job market came with a self-imposed period of nickel-and-diming. I think the best example of this is the choices I made when picking a work laptop. My employer had a great policy on laptops, and tools in general, which went roughly like this: We trust you to be reasonable and choose an appropriate tool for the job, here’s the company card.

Okay this is a minor tangent, but if you trust someone enough that you price their time at hundreds of dollars an hour, you should trust them enough to make a reasonable decision when they buy a computer. Creating a list of approved computer models and sub-models and making sure it stays updated is not only a waste of time, but an admission that even after two screenings, four interviews and seven reference checks you don’t trust your newly hired developer to have a functioning brain. Please explain to me how that makes any fucking sense (using the company’s approved list of arguments).

Anyways, back to the story. Most of my soon-to-be-colleagues used MacBooks, and as someone who had been on Windows my whole life I was excited to check out the dark side and spec out my new MacBook Pro. This was a little while after Apple started shipping their own silicon, and I (correctly) assumed the base MacBook Pro CPU option would be more than enough for my needs. Where I went wrong was in thinking that 16GB would be plenty. I had heard from some seniors that I might want to get more, but when I saw the outrageous upgrade prices I decided 16 would probably be fine. I don’t remember the exact prices, but I think I would’ve had to shell out something like $400 USD more to get to 32 gigs, which I found (and still find) absolutely outrageous.

So I made the fiscally conservative choice, and boy have I felt the consequences of that over the last three years. Spinning up the containers required to run our platform locally casually eats up at least half of my memory, and the fact that every application on the face of the planet now runs in Electron means the other half is in heavy demand. IntelliJ currently takes 3-5 business days to static analysis after I make a change, presumably because it’s getting approximately two millimeters of that precious RAM stick.

Suffice to say, I’ll make sure to not skimp on specs next time, but this is just one way to illustrate the larger point. If a carpenter goes out to buy a circular saw, you can bet your ass it will be a good circular saw. We should have the same attitude with our tools. (”Tools”, in this case, doesn’t just refer to our hardware, but also software and services that make us more effective.)

I would be willing to bet my 16GB MacBook Pro on the assertion that 50 developers with a yearly budget of $2,000 to be used on tools, courses and whatever else they need to create good products fast will be vastly more productive than 51 developers with a budget of $0, despite the company’s costs being the same in both cases. Oh, and as an added bonus your employees will be a lot happier if they get to develop their skills and use high-quality tools, so you’ll get to spend less money on having recruiters trawl LinkedIn for new victims employees to revoke the Figma licenses of. The fact that payroll usually makes up the vast majority of the costs in our field means that any purchase that lets developers be just a little bit more productive is suddenly worth an absolute boatload of money. The amount of leverage in these kinds of trade-offs is fucking absurd.

Cruel and unusual punishment

It seems that I have subconsciously ordered these three main sections in increasing order by how much wrath they incur in me. Because, I swear to god, I am going to lose my entire fucking mind (all of it) if I get called into another hour-long three-person meeting discussing whether to go ahead with something that literally costs less than the time spent on that meeting. Yes, that’s something I’ve been subjected to, and yes, it felt absolutely bizarre. Even if the question had been whether we should set fire to $200 it would’ve been more financially responsible to just light the fucking bills than to discuss it for that long.

The only reason a meeting like that could ever be allowed to happen is that the meeting’s creator forgot just how stupidly expensive meetings are. And look, I’m not saying we shouldn’t ever have meetings. Some meetings are necessary, some are useful, and I’ve been in plenty of meetings that have resulted in important revelations, improved collaboration and higher productivity. Personally, I subscribe to the idea that meetings are a tool to make people talk to each other about a certain topic, which should only be used as a last resort. If your team already keeps each other up-to-date on what they’re working on and notify people about their blockers you can probably axe that stand-up from everyone’s calendar.

Another side-note (and I promise this is a short one): Why is “any blockers?” a standard part of the stand-up formula? If you encounter something that stops you from progressing, just ask the person you need help from right away. Why would you wait until tomorrow’s stand-up? Are there actually any people who encounter something that stops them from progressing on a task, and in response to this new-found adversity just sit there helplessly, idling like a horse in Oblivion until someone finally asks them about blockers?

This is all kind of besides the point, though. This particular crusade isn’t about teaching people which meetings are worth having (that’s something I wish I was better at understanding, myself). As you might have noticed from the previous section, I’m very much in favor of letting people make their own, informed decisions and trusting in our ability to hire people who usually make good ones. Therefore, instead of telling you which meetings to have and not have, I’ll settle for helping you visualize how expensive your meetings are, and letting your judgement take it from there.

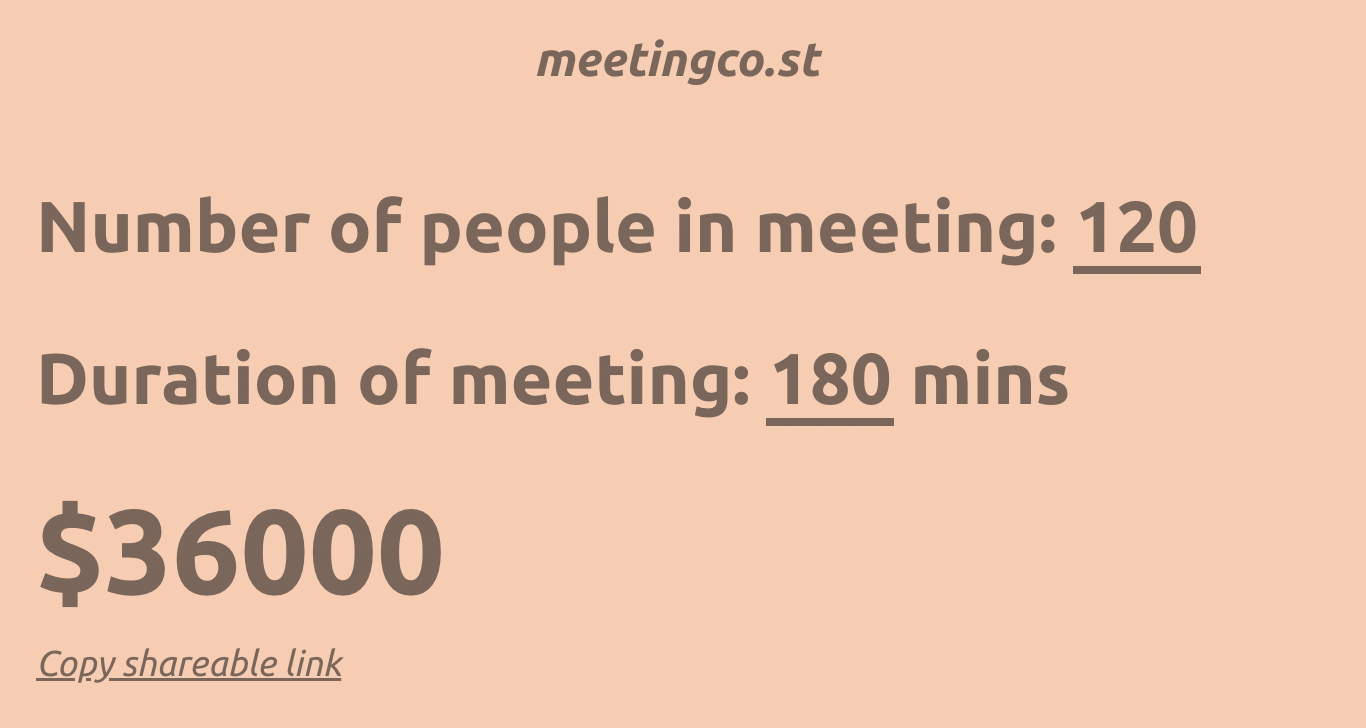

The inspiration behind how I plan on doing exactly that actually goes back to what is almost certainly the most expensive series of meetings I’ve ever been a part of. A few years ago, the division I was a part of at my client company, which at that point consisted of around 120 people, held mandatory division-wide demo meetings. These usually lasted at least three hours, and consisted of every single team being assigned something like 10 minutes to go through everything they’d done the last two months. I’m sure the organizers had good intentions, and cross-team communication really was lacking at the time, but most people I talked to understandably found these meetings to be — to put it diplomatically — an interesting way to spend their time.

It was during one of these meetings that I was struck by the thought that someone really oughta make a live-counter you can start in the beginning of a meeting to see the dollars tick away. So I registered my first São Toméan domain, meetingco.st, and promptly let the domain lay dormant for well over a year. (Hey, don’t judge. May the developer who actually uses all their domains cast the first stone.) As I started writing this blog post and realized a rant about meetings was inevitable, I figured it was as good of a time as any to finally get that website out of the door. It lets you calculate how much a meeting costs, given a duration and number of participants, and even lets you start a live counter to remind everyone (or just yourself) of how much money is being spent in real-time. By popular demand it also has a “make a shareable link”-button, so you can passive-aggressively include your calculation in your response as you hit “accept” on yet another pointless but mandatory meeting in your Outlook calendar.

The domain meetingco.st was registered roughly $20,000 into a $36,000 meeting.

The cure

The cure for speed blindness, according to Norwegian driving education syllabus, is to actively make use of the speedometer. We’re taught to keep an extra eye on it as we exit the highway to ensure we stay within the speed limit while we give our brains time to adjust to the new speed.

For a while I’ve wondered what the equivalent to a speedometer check is in a software development company. Being able to recommend a simple method that can protect against the payroll fallacy would not only provide this blog post with a satisfying conclusion, but I think it would be damn useful in my own career. Disappointingly, it seems like the world is once again complex, and that the answer is that it mostly depends.

I do, however, think that we would all do well to try to remember that since payroll is a cost like any other, developer time is a currency, and one we should spend wisely. I think this is especially important to remember when we’re presented with opportunities to spend dollars and get developer time in return, because often times the exchange rate is way better than what you get by hiring your 51st developer.